- Home

- David Ramirez

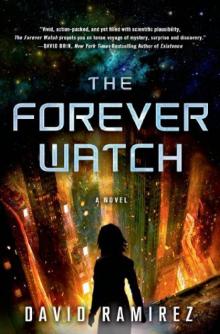

The Forever Watch

The Forever Watch Read online

THE FOREVER WATCH

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

THOMAS DUNNE BOOKS.

An imprint of St. Martin’s Press.

THE FOREVER WATCH. Copyright © 2014 by David Ramirez. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.thomasdunnebooks.com

www.stmartins.com

Design by Steven Seighman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data (TK)

ISBN 978-1-250-03381-9 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-250-03382-6 (e-book)

St. Martin’s Press books may be purchased for educational, business, or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases, please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at 1-800-221-7945, extension 5442, or write [email protected].

First Edition: April 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Liza,

Who kept believing

And my father,

Who never got to read this

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I never would have gotten this far without all the people that drew the writing out of me when I was growing up, and the individuals who saw something in this story and made it happen. It’s not a complete list at all—that would be its own book.

Thank you:

To mom, my wife, and friends: they make it possible for me to try

To the AS Hill crowd: they got me writing when I was supposed to be studying science

To Auraeus Solito: the first teacher to make me believe I had something in me

And to Kristin Nelson and Peter Wolverton: they brought the book home

THE FOREVER WATCH

1

Functional, slightly uncomfortable plastech bedsheets cling where the hospital gown exposes skin. The air is cool and dry against my face. My muscles feel heavy, cold, unwieldy. The air whispers through the vents, the devices beside me hum and buzz and beep. My eyelids are slow to open. Orange glimmers streak back and forth across my vision, as the Implant starts to pipe signals into the optic nerves.

Waking up has been odd since the last of the post-Duty surgeries were completed. The Doctors tell me that it is primarily due to the hibernation, and to a lesser degree, the medication altering the timing between the organic and inorganic parts of my brain.

Menus come alive, superimposed over my vision.

My mental commands, clicking through the options and windows and tabs, are sluggish. Despite the chemical interference, the Implant processes my thoughts, assists me in revving up the touch center of my mind. To my left, the curtains slide open, brightening the room further. Normally, I can do this without going through the interface, but I cannot muster the concentration right now.

It is the end of the week, the last day of my long, long “holiday.” If my evaluation goes well, I can go home.

A thought about the time pulls up a display. There are hours yet.

Breakfast is on the table by the bed. Oatmeal, an apple, a biscuit, a packet of margarine, and a carton of soy milk. I could float it over and eat without getting up, but I’ve been on my back for too long. I force myself upright and swing my legs over. On my feet, the world sways, left and right. But it is not as bad as the first day I woke up after restorative surgery. Four days ago, even sitting up induced nausea.

Eating is a slow ordeal, each motion requiring my complete attention. My hands still shake. The milk sloshes when I raise it to my lips. A little trickles between my numb lips. I can barely taste the food. Is it the typical bland hospital food, or is it the meds?

An hour to eat and I am already tired, but I do not want to sleep. There is a rehab room where I could exercise for a bit. There is an inner courtyard garden where my fellow post-Duty patients are walking around in the sun, talking through what we’ve been through. I do not want to talk. I do not want to play cards with the other patients. I want out.

A few command pulses tap me into the Nth Web. My body is left behind a cramped desk, but I fly through the glittering mazes of dataspace, a world made of light and information. At my bookmarked sites, I look into what has been happening while I slept. There is little to catch up on. The weather is as expected. There are articles about performances in the theaters, and petty crime being on the decline, and the usual updates about the Noah’s vital systems. All good, situation nominal.

A little more awake now, I open a music application and try to listen to Thelonius Monk. I cannot enjoy it; my emotions are still too dulled. I try an old movie about cowboys for two hours’ worth of distraction. Shop for replacement parts for the coffee grinder I was not able to fix before I was picked up by the Breeding Center.

Knocking at the door. Old forms from another age. A lost world.

“Come in.” My voice still startles me. Did I always sound like this?

“Afternoon, ma’am.”

The orderly delivers lunch, picks up the breakfast tray. I notice a little cupcake on the corner, with a lit candle.

“Your last day, right?”

“Yes.”

Baby face. Too young. He tries his best charming smile. “Maybe I’ll see you around on the outside.” Not very subtly, he messages me his ID along with my copy of the receipt for today’s meals. In my head, the packet includes a little attachment. My. He is confident about his body. “Maybe.” I wonder how many women give him a call afterward.

“Well. Bye then, Ms. Dempsey.”

I don’t want to eat any more. Should have gotten up earlier instead of putting off breakfast. I make myself eat the salad. I spear and consume every bit of lettuce and drink the last mouthful of chickenish broth. The Behavioralist will notice if I don’t.

A hot shower makes me feel marginally more alive. Almost scalding hot. I try to enjoy the water crashing down on me, until the system automatically cuts it off when I have hit today’s limit. A wireless transmission through the Implant authorizes a debit to my accounts, and I indulge in a half hour more, until my fingers and toes wrinkle up.

The hospital towels are coarse. In the mirror, there I am. Thinking of the past, and the device in my head.

Behind the wall constructed by the meds, emotions are boiling up, seeping through. I need, desperately. Need what? Maybe nothing. Maybe it’s just neurotransmitters pinging off each other in my head. But real or not, despair is bubbling up through the artificial calm.

I resort to the one memory that has always been a comfort to me—that first moment after waking from the neural augmentation.

The neural Implant is a web of nanoscale threads spread through the brain. The bulk of it forms a dense network on the outer surface of the skull. Through an X-scanner, it looks like a flower, blooming from a stem rooted at the base of the brain close to the chiasma of the optic nerve, with silvery transmitter petals that open up over the skin of the face.

Pre-psi-tech, the closest analogue is working with a computer, which is still how pre-Implant children do their homework, access the Nth Web, entertain themselves. The Implant too is a computer, except that the control devices are not manipulated with the hands. The cpu is part of the brain, responding to thoughts rather than key presses and button clicks. Instead of being displayed with a monitor and speakers, the information is written into the mind and onto the senses. It is a constant passenger linking me to a larger world. Data, communications, and perfect memory recall all just a thought-command away.

There is a qualitative difference before the device is implanted, when memories are blurry and fluid, and after, when they become concrete and immu

table. They can be accessed in slow motion or fast-forward, or searched with database queries. The stimuli of the senses are preserved in perfect slices with a clarity that will never diminish as the years separate me from them. The transition between merely human recall and enhanced experience is sudden.

Automatic scripts take over my bodily functions, lock my nerves, and prepare me for full reimmersion. I go back to that when, to that me.

I have my Implant!

Looking in the mirror, my eyes are itching and a little red, and I think I will cry.

Not that I was very pretty before the surgery, but I was hoping for something … cuter … than what I got on my face. There’s too much chrome! I touch my reflection. There is a metallic eye drawn on my forehead. And under my eyes, following the edges of my cheekbones, are a pair of flattened triangles that start just to the sides of my nose and spread out toward my temples. My lips are just barely dusted with silver.

What does it—oh!

Just as I start to wonder, the interface opens up in my head. Menu bars and buttons light up across my field of view. I remember from the pre-op orientation that those are just symbols. It’s the thought structure in my head that matters, the way the biological electrical pulses along the neurons talk to the hardware poking into the synapses in between.

Blurring flashes in my eyes, chaos, colors, pictures, text, sounds in my ears. The passenger is listening, but it doesn’t know which of my thoughts to pay attention to, so it tries to respond to all of them.

“Think disciplined,” Mala said to me, over and over, when I was growing up. “No stray thoughts. Keep the mind empty except for what you need.”

A long, dizzy minute passes while I get a grip. Like everybody else, I have been drilled with meditation, visualization, and biofeedback, practice for keeping my thoughts from jumping all over the place. The interface steadies, and my vision clears.

The Implant receives my awkward, slow questions. It accesses the Noah’s systems and informs me. Data pours into my head. One hand braces against the sink, and the other touches my reflection. Orange arrows appear and highlight the emitter-plates on my face.

The silver eye indicates that I have some talent for reading and the lips indicate writing. From the size and density of the exposed filaments, I only have enough for neural-programming on the Nth Web—no poking around in others’ heads or making them do what I want.

The triangles on my cheekbones, which are bright and large, indicate that the majority of my talents lie in touch. I can reach out with my thoughts and manipulate objects without my hands. Ooh. My projected power-output suggests that I will be pretty strong. Lifting a car with my mind is not out of the question, if I have the correct amplifier to boost the signal. Oh! I’ll be getting my first amplifier today. No more watching enviously while the older kids play crazy, physics-defying games—no-hands baseball, psycho-paintball, ultra-dodgeball …

The ugly pattern of chrome on my face is starting to seem a little less uncool.

Lastly, there is the bit I did not notice—a tiny, shining teardrop right in the corner of my left eye, which is correlated with guessing. I have just a little bit more intuition than most.

The red toothbrush in the mug to the side of the sink catches my eye. I squint at it and think hard at it, remembering my lessons. It starts dancing, makes a clinking sound as it whips from side to side against the ceramic.… This really, kind of, somewhat rocks, and as I manage to float the toothbrush to a jerky kind of hover in front of my face, maybe it’s even the height of boss.

I think of all the funny words and phrases from the movies of lost Earth that Mala watches with me, but the ones I want are from before the Implant, and they’re fuzzy and hang just at the tip of the tongue. It’s centuries later, and just like everything else on the ship, the slang gets recycled too.

That was that, and this is this. The rest of my life.

The loss of concentration releases the toothbrush. It falls and clatters around the drain.

I focus on my face again. Maybe it’s not so bad. The chrome brings the sepia and umber highlights out of the brown skin and makes my round face a little sharper, a bit more adult. The green eyes look brighter because the cheek-plates catch some of the light and reflect more of it onto my eyes at an angle, and it brings out the hint of orange-jade at the edges of the irises. Maybe it doesn’t look too bad with the white-yellow hair either, makes the long waves seem less like generic blond and more like something with an exotic name, such as maize.

Someone is knocking on the door. I know, without a reason why, that it’s Mala.

“Come in!”

It is. She stands behind me and puts her hands on my shoulders, bare in my patient’s shift. Her palms are warm but her fingers are cool. She’s smiling with her eyes but not with her mouth.

“You’re growing up.”

Then I am crying, and I don’t know why, and she’s crying and hugging me.

I trigger the cutout procedure, and my sensorium returns to now.

Here I am, in another hospital, looking in another mirror—only, I am thirty years old.

I know now why Mala was crying that day I was twelve and marveling over my new Implant and my shiny future. Because she would have to let go of me soon. Because I would forget her, too busy with training school and new friends and all the great things I would do with my talents, which put me squarely beyond the ninety-fifth percentile: one of the ship’s elite, requiring earlier and more demanding training.

Life, she had told me, only went forward. But the Implant’s memory features defy that. An idle thought relives a past moment as if it were the present. The distinction between yesterday and decades ago seems only a matter of semantics.

Now, I am not looking at my face. I am looking at my body.

It is as if nothing has changed between my going to sleep nine months ago, and my waking up today. Only Doctors with the strongest healing handle Breeding.

My arms and legs are smooth and wiry, the muscles not at all atrophied, despite the long period of inactivity. No scars or stretch marks cross my belly. My breasts are not particularly swollen or tender. I look down and cup the folds of my sex, and they are the same color, the inner lips the same size, and internally, when I clench, the muscles tighten around my fingers and the fit is snug.

It is as if I were never pregnant, as if I had not given birth mere days before.

I am crying, and the tears are hot. Mala is not here with me, and I do not want to see the Behavioralist waiting in the receiving room.

For women on the ship, Breeding is a duty and a privilege. Fertility is perfectly regulated. There are no slipups.

Perhaps there was with me. I am not supposed to feel any different now. It is supposed to be a long, paid vacation spent asleep. During that time, a woman’s body is just a rented incubator. That’s all. The baby may not even have been made with an egg from my ovaries. The father could be any of the thousands of male crewmen with favorable genetics.

Somehow, I know. Despite the lack of physical evidence, I know it in my body, in the flesh.

I have a baby out there.

Behind the meds, there is a longing to hold something tightly. There is a yawning cavity inside my body, which was filled and stretched, and now is empty.

I wash my face carefully and put on the patient’s gown. Pink for a female—comfortable and warm. I bite down on the resentment of how much easier this is for male crew members. For them, Breeding Duty is a bit of awkwardness that can be done away with during a lunch break.

When I walk out and take my seat, the woman in the deep-green coat and spectacles processes me. She asks me the same questions I filled out on the form. I answer the same way. I smile and nod where appropriate.

But there is no deceiving a professional. The eye on her forehead is three times the size of her biological eyes, and the silver coat on her lips is solid, gleaming chrome. The circlet she wears glows green and gold and is actively drawing on the Noah’s

power. She reads me with the combined insight of centuries, empirically derived heuristics analyzing my posture and the muscle twitches on my face, as well as the mind-bond forged by her psychic ability and amplified by the circlet. Empathic and telepathic probes slide through my head with the delicacy and grace of a dancer prancing around onstage.

“Ms. Dempsey, it seems as if Dr. Harrison was a touch too conservative with the suppressors, that’s all.”

“Which means?”

“What you’re feeling is just a by-product: traces from a slight amount of telepathic contact with the fetus. It’s not supposed to happen, but no Breeding is exactly the same. Some embryos are stronger than others. It’s nothing physical. Dr. Harrison assures me that your hormones have been rebalanced and stabilized.”

“I see.”

“No need to feel so anxious, Ms. Dempsey.” She licks her lips and her fingers tap away at the black slab of crystal in her hand.

This Behavioralist is more practical than Dr. Harrison was. He liked to show off and gesture and point in midair.

The psi-tablet she uses is an interface device for accessing the ship’s systems. Though everything can be done directly through the Implant, it takes continuous concentration and focus to do so—any misthought comes through as an error, can cause a typo in a document or slide in incongruous data, a flash of imagery, a scent, a taste. The psi-tab and larger hard-line desk terminals are easier to use for long durations, and for certain applications they can be endowed with stronger security than the sometimes leaky interface of discrete data packets passing between wetware and hardware.

“There we are. I’ve modified your prescription. The system will ping you with reminders when to take it. The orderly will administer a dose just before you are released. More will be in your mailbox in the morning. Be sure to follow the instructions.”

The Forever Watch

The Forever Watch